This is another common question we frequently receive. Can I patent an app? The answer, as with many other questions regarding the patenting of software, is very dependent on the specific case.

While in many territories around the world, software itself is excluded from patentability as “non-technical”, this does not necessarily mean that patenting of software-based solutions to technical problems is impossible. There are many possible strategies, but it is likely to be more difficult than standard engineering-based inventions.

What exactly constitutes a technical problem is in itself vague. In the context of software patenting, one approach is to cast or formulate the technical problem in terms of the manipulation of electronic data which relates to the processing of physical data. For instance, an app for the improved reading of a QR code could be patentable matter.

Software also is likely to offer a solution to a technical problem if it affects the operation of the computing hardware generally; this would include apps which modify background system processes to improve operating system performance for instance.

In this article, I will briefly outline the current legal status of software patent applications in the UK and elsewhere, before exploring a case study of a recently granted British patent for a mobile phone app.

Current status of software patent applications in the UK

The current state of software patent law in the United Kingdom is based on the decision in Aerotel v Telco and Macrossan’s Application in 2006. In the judgment of the British High Court, a new four-step test for patentability was introduced:

- Identify the intended meaning of the claim.

- Identify the contribution which the invention as described in the claim makes.

- Consider whether the contribution falls solely under one of the formal exclusions in the Patents Act

- Consider whether the contribution is technical in nature

In this case, Aerotel’s patent covered a new form of telephone exchange, and required software. It was judged that the invention was not limited to non-technical subject matter (the software), but also included patentable technical subject matter in the exchange hardware, and therefore was not excluded.

Macrossan’s Application, which related to software for automatically registering businesses, was ruled to be excluded, as the software was applied in the solution of a non-technical problem – the registration of a business.

Of course, the applicant must also demonstrate that their invention is novel and inventive to receive a patent. Meeting the requirements of the four step test is only sufficient to avoid summary rejection under the excluded matter provisions.

Other jurisdictions

The UK’s rules regarding software patents are fairly strict compared to most jurisdictions. If you are considering applying for a software patent, it may be worthwhile discussing a European patent instead, which can be validated and thus enforced in the UK (Brexit will have no effect on this).

The European Patent Office’s test for exclusion is simply whether the application presents “an invention in a field of technology”. Technical effect is judged in principal in a similar way to the UK, but in practice there is a far wider range of case law to draw from, and it is thus typically easier to demonstrate technical effect during prosecution.

Other jurisdictions are potentially less strict regarding these exclusions. In the United States, novel and inventive applications of algorithms are considered patentable. Japan and South Korea are also generally more friendly to software patent applicants.

A brief review of a UK mobile app patent – GB 2515096

UK Patent 2515096, “Methods and apparatus for allowing a mobile computing device to interact with an online portal”, issued to Giovanni Maria Laporta, is a good example of effective mobile app patent prosecution in the UK.

Apps are widely available which allow users to check in to a physical location using their phone. The most widely used of these is FourSquare®, which generates suggestions of restaurants and entertainment venues based on those which users frequent. FourSquare uses a proprietary software package, called Pilgrim, which checks-in its users to venues based on their GPS location. However, mobile phone GPS requires a data connection, and may be unreliable or slow for users, especially if they have old or budget smartphones.

Figure 1 of GB2515096, showing the interaction of the phone with the store’s server

Laporta’s inventive concept is simple: the user should log in to a Wi-Fi network provided by the location, and the app should send a signal over the location’s Wi-Fi network to a local computer. The app then automatically loads a page (the internet portal) displaying information about the location, including a check-in button.

While this may well be an improvement over FourSquare’s technology, you may find it surprising that this was found to be patentable, given the requirement for the patent to cover technical matter. After all, the same effect would virtually be achieved by setting the homepage of the local Wi-Fi network to the internet portal! Let’s have a look at the granted claim 1:

A method of allowing a mobile computing device to interact with an online portal for a entity, comprising the steps of:

receiving an RF signal sent from a wireless local area network at a location of an entity, the RF signal including a first identifier for the wireless local area network;

the mobile computing device sending a first signal to a server, the first signal including the first identifier; and the server, on receiving the first signal including the first identifier, determines the entity associated with the first identifier and allows the mobile computing device to interact with the entity’s online portal.

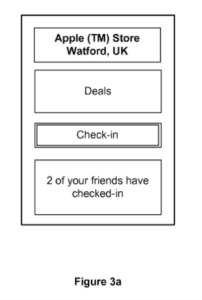

Figure 3a, with a schematic of a user interface for the app

The first thing to note is that the claim is framed entirely in technical language. Although terms such as “RF signal” may seem strange in this context, they are intended to reinforce the Examiner’s initial perception that this is a patent application about a method which has effects in the real world; describing the app’s function in terms of the transmission of signals is one of the simplest ways to achieve this.

Another important point is the use of object language such as “first identifier” and “first signal”. This is an effective strategy in software patenting; instead of a mundane data package, the language suggests a specific, concrete interaction between hardware. It is particularly effective for this claim to be set out as a method claim, because it is obvious that the hardware to achieve the invention is not new. The applicant was able to successfully prosecute the patent by claiming novel and inventive uses of known hardware.

There are other methods of pursuing protection for an app. Claim 17 of Laporta’s patent indirectly claims the app, but is designed as a claim on the hardware:

A mobile computing device comprising a communications interface configured to receive an RF signal from a wireless local area network at a location of an entity, the RF signal including a first identifier for the wireless local area network; a processor configured to cause the communications interface to send a first signal to an external server, the first signal including the first identifier for the wireless local area network; and a display configured for displaying an online portal for the entity.

The distinguishing feature of this claim is the communications interface as configured, which can only be inferred as a reference to the application. However, by claiming the mobile computing device instead, the technical character of the invention is emphasised; it would be difficult for the Examiner to reject a claim which explicitly covers hardware on excluded matter grounds. Claiming the programming of the app in terms of the configuration of the communications interface is similarly advantageous; while algorithms are not patentable in the UK and other territories, preconfiguration of the physical state of a device is.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can see that it is indeed possible to receive patents on mobile apps in the UK, as long as the app is suitably novel and inventive, although it is important to draft the claims carefully to avoid excluded matter objections.

If this article was of interest, then please also have a read of our article on Google’s recent AI patent applications. And, if you have any questions or feedback, please do contact us; we’re here to help you succeed.