We are pleased to be supporting Camborne Trevithick Day on 27th April 2019. This annual celebration commemorates Camborne’s most famous son, prolific inventor Richard Trevithick. The first commercially useful steam engine was developed in 1712 by Thomas Newcomen, and improved by James Watt and others throughout the 18th century. By the time Richard Trevithick began his professional career steam was already powering the industrial revolution – but Trevithick made critical improvements to efficiency and demonstrated the first working steam locomotive. This laid the groundwork for George Stephenson’s famous locomotives and the development of the railway in the UK and around the world.

Full details of the event, including how to get there and where to park, may be found at the organiser’s website https://trevithickday.org.uk/. Perhaps you will be inspired – as Cornwall’s newest patent attorney firm, we certainly hope that Richard Trevithick is not the last great inventor from Cambourne!

In the meantime, we thought it would be interesting to look at the legal side of Trevithick’s career.

Trevithick seems to have spent rather a lot of time trying to navigate patent law. Initially, it was someone else’s patents – those of James Watt – which proved to be a thorn in Trevithick’s side. As long ago as 1624, the law had set a maximum term for patents, but Watt managed to get an Act of Parliament to extend his protection for “A method of lessening the consumption of steam in steam engines” until 1800. The nub of Watt’s patent was the separate condenser, something which led to improved fuel economy over the old Newcomen engine.

Towards the end of its extended term, it appears that Watt’s patent was being widely ignored in Cornwall, with various mining engineers adding separate condensers to old Newcomen engines. Watt sued and, in theory at least, eventually won.

The expiry of the Watt patent in 1800, coinciding with Trevithick’s own pioneering use of high-pressure steam, represented an opportunity, and his experience with Watt had no doubt left an impression. There is a story – probably completely unverifiable – that on being served with an injunction Trevithick held Watt’s lawyer upside-down over a mineshaft. Trevithick evidently did not gracefully accept defeat but had surely learned the power of the patent. What’s more, the litigation over Watt’s patent lead to the important legal principle that a valid patent could be granted for an improvement to a known machine. Trevithick could turn this to his advantage.

After refining his high-pressure engine, Trevithick naturally sought to obtain his own patent. In January 1802, with his cousin and business partner Andrew Vivian, Trevithick went to London and asked around for someone who knew how to get one. This does not seem to have been an easy job and required personal attendance at multiple offices. Trevithick was a busy man, visiting Merthyr Tydfil and Coalbrookdale in the same year, so it was Vivian who took his place in London and in March 1802 wrote to report that he “must call at the Patent Office for the great knob of wax”. In those days there was no actual examination of a patent application to check that it was for a new invention, but the Patent Office made up for this in impressive bureaucracy. Nowadays you get the photocopied signature of a middling civil servant in place of that great knob of wax.

Trevithick also took Watt’s lead when it came to charging for the use of his now patented invention. Like Watt, Trevithick agreed with mine owners that he would be paid a percentage of the money saved on coal by the use of his modern and efficient high-pressure engines. Unfortunately, after returning from his tour of the Americas, Trevithick found that his customers had simply stopped paying, variously claiming that they thought the patent had expired, or that it did not cover some variation in the boiler design. Trevithick managed to negotiate with a few, but – unlike Watt this time – did not pursue the matter in Court.

Trevithick nevertheless filed for patents throughout his career, ending up with fourteen to his name. His first patent, of 1802, was numbered GB2599, in a sequence that starts with GB1 of 1617. By the time Trevithick had obtained his last patent in the year before his death, the number was at GB6308. More patents had been filed in Trevithick’s career than in the 200 years previous. The age of technology had certainly arrived.

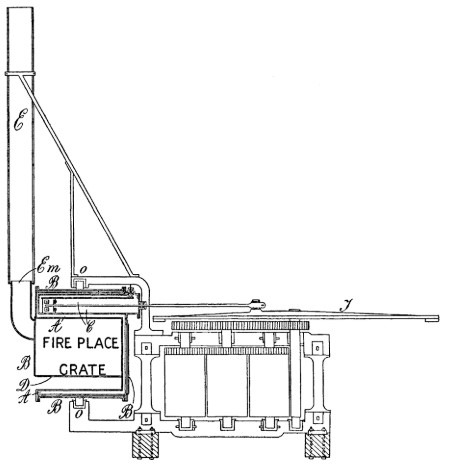

Illustration from Trevithick’s 1802 patent specification